Quick Summary

Table of Contents

The Delhi Sultanate is a wonderful chapter in Indian history. This ancient Muslim kingdom, which flourished from the 13th to the 16th century, played a key role in forming the socio-political landscape of the Indian subcontinent. With its beginnings in battles and cultural exchanges, the Delhi Sultanate left an indelible impression on the location’s records. This article dives into the multiple components of the Delhi Sultanate, consisting of its history, management, and government, dropping mildly on the details that marked this fascinating era.

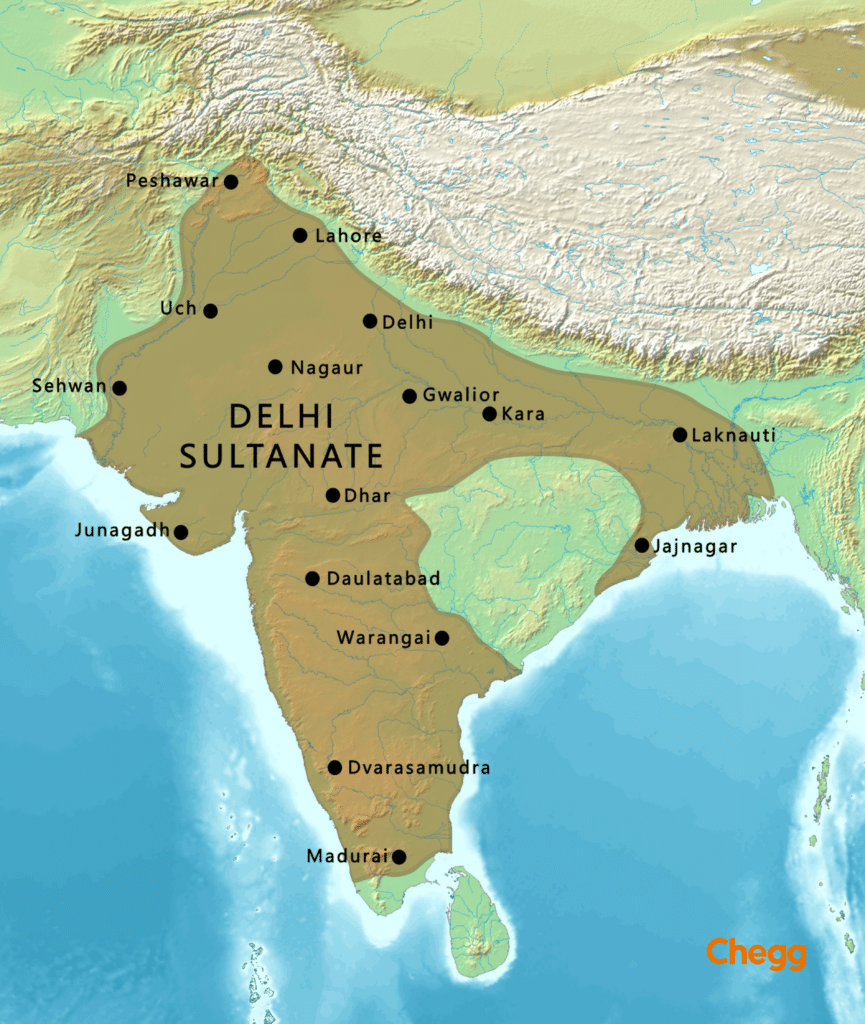

Between 1206 and 1526, the Delhi Sultanate, an Islamic Empire, governed South Asia, primarily the Indian subcontinent, with its epicentre in Delhi, an ancient city in Northern India. Historians divide the Delhi Sultanate’s reign into five distinct dynastic periods.

The empire’s inception is rooted in Turkic migration, a widespread phenomenon during the Middle Ages, where Central-Asian ethnic Turks spread across Eurasia, integrating into the cultures and political systems of dominant nations. Often, Turkic migrations were not voluntary; some Turks were compelled to leave their homelands.

Qutb-ud-din Aibak, a well-known naval commander who served under Muhammad Ghori, founded the Delhi Sultanate. Following Ghori’s death, Aibak hooked up the Slave Dynasty and rose to strength because of the first Sultan of Delhi. Aibak’s rule marked the beginning of the Sultanate’s rule, starting up a Delhi sultanate period of great political and cultural ameliorations.

The established order of the Delhi Sultanate may be credited to the turbulent political scene of the Indian subcontinent in the twelfth century. The attacks by Turkish and Central Asian masters, mainly Muhammad Ghori’s operations, weakened current local forces. The Battle of Tarain in 1192 marked a crucial moment in which Ghori’s win over King Prithviraj Chauhan made way for the established order of the Sultanate.

Also Read:-

The Delhi Sultanate is a significant record in Indian history, defined by its active masters, cultural fusion, and lasting effect and for many centuries, the Delhi Sultanate period followed several families’ rise and decline, leaving a permanent impact on the Indian region.

The Delhi sultanate period they were extended from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century, lasting roughly 3 centuries. It marked a changing time in Indian records; at some stage, numerous kingdoms set up their rule over the location.

The Sultanate’s established order was based on the aftermath of wars by Turkish and Central Asian masters, leading to the established order of a series of effective Islamic powers.

| Dynasty | Time Span | Emperors | Famous Incidents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mamluk (Slave) Dynasty | 1206-1290 | – Qutb-ud-din Aibak (Founder) | – Ottoman-Mamluk War (1485-1491) |

| – Shams-ud-din Iltutmish | – Ottoman-Mamluk War (1516-1517) | ||

| – Razia Begum | |||

| – Muizuddin Bahram Shah | |||

| – Alauddin Masud Shah | |||

| – Nasiruddin Mahmud | |||

| Khalji Dynasty | 1290-1320 | – Jalal-ud-din Khilji (Founder) | – Attacks on Ranthambore |

| – Alauddin Khilji | – Siege of Chittorgarh | ||

| – Mubarak Khilji | – Capture of Mandu | ||

| Tughlaq Dynasty | 1320-1414 | – Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq (Founder) | – Invasion by Timur (Tamerlane) |

| – Muhammad Bin Tughlaq | – Turco-Mongol incursions | ||

| – Firuz Shah Tughlaq | – Nasiruddin Mahmud | ||

| Sayyid Dynasty | 1414-1451 | – Khizr Khan (Founder) | |

| – Mubarak Shah | |||

| – Muhammad Shah | |||

| – Alam Shah | |||

| Lodi Dynasty | 1451-1526 | – Bahlol Lodi (Founder) | – Battle of Panipat |

| – Sikander Lodi | |||

| – Ibrahim Lodi |

Enslavement of individuals from non-Muslim regions became prevalent in Middle Eastern Islamic societies during the Middle Ages, as enslaving Muslims was prohibited. Many Turks were subsequently transformed into Mamluks, or “slave warriors,” serving the Middle Eastern caliphates. Notably, the Delhi Sultanate’s first ruler emerged from this Mamluk background, showcasing the diverse origins and influences shaping the empire.

| Ruler | Period | Key Contributions and Events |

|---|---|---|

| Qutub-ud-din Aibak | 1206–1210 CE | – Founder of the Slave Dynasty and the Delhi Sultanate. – Faced challenges from Tajuddin Yaldauz and Nasiruddin Qabacha. – Known as “Lakh Baksh” for his generosity. – Made Lahore his capital and started the construction of Qutub Minar. – Died playing polo in 1210 CE. |

| Aram Shah | 1210 CE | – Son of Aibak. – Ruled for only eight months due to incompetence and was eventually replaced by Turkish nobility. |

| Iltutmish | 1210–1236 CE | – Initially a slave of Aibak; later appointed governor of Gwalior. – Dethroned Aram Shah in 1211 CE. – Consolidated Turkish rule, defeated rivals, and saved the Sultanate from the Mongols. – Completed Qutub Minar and introduced silver tanka coin. – Nominated daughter Raziya as successor. |

| Ruknuddin Feruz Shah | 1236 CE | – Eldest son of Iltutmish. – Briefly ruled with support from nobles. – Overthrown by his sister Raziya during a rebellion in Multan. |

| Raziya Sultan | 1236–1239 CE | – First and only female ruler of the Delhi Sultanate. – Faced opposition for appointing non-Turkish nobles and discarding traditional customs. – Captured by Altunia, later married him but was eventually defeated and killed by Bahram Shah. |

| Bahram Shah | 1240–1242 CE | – Son of Iltutmish; rose to power after Raziya’s fall. – His reign was marked by struggles with Turkish nobles. – Killed by his own army. |

| Alauddin Masud Shah | 1242–1246 CE | – Son of Ruknuddin. – Ineffective ruler, eventually deposed in favour of Nasiruddin Mahmud. |

| Nasiruddin Mahmud | 1246–1265 CE | – Grandson of Iltutmish; ruled with support from Balban. – Balban became the de facto ruler, possibly poisoning Mahmud to seize power after his death. |

| Balban | 1266–1286 CE | – Reinforced monarchy’s power, declared Sultan as God’s representative. – Established strict court protocols and a spy system. – Focused on law and order; crushed revolts, especially against Mongol threats. – Died in 1287 CE. |

| Kaiqubad | 1287–1290 CE | – Grandson of Balban; supported by nobility. – Brief reign; murdered by Jalal-ud-din Khalji, who established the Khalji Dynasty. |

| Ruler | Period | Key Contributions and Events |

|---|---|---|

| Jalal-ud-din Khalji | 1290–1296 CE | – Founder of the Khalji dynasty, came to power at 70 after serving as warden of northwest marches. – Successfully defended against Mongol invasions during Balban’s reign. – Aimed to soften harsh policies of Balban, ruled with tolerance. – Pardoned rebels, including Malik Chhajju. – Murdered by his nephew Alauddin, who seized the throne. |

| Alauddin Khalji | 1296–1316 CE | – Assassinated Jalal-ud-din to take power. – Reversed tolerant policies, implementing strict laws to prevent rebellions. – Built a strong army; and defended Delhi from six Mongol invasions. – Expanded the empire by conquering Gujarat, Ranthambore, Chittoor, Malwa, and parts of Rajputana. – Led expeditions into the Deccan, bringing immense wealth. – Patronized poets and built architectural marvels like Alai Darwaza and the city of Siri. |

| Alauddin’s Administration | – Reformed military and economy; soldiers paid in cash. – Established four markets in Delhi, regulated prices, and stored grain supplies. – Introduced land measurement for revenue collection in cash, influencing future reforms by Sher Shah Suri and Akbar. | |

| Qutbuddin Mubarak Shah | 1316–1320 CE | – Son of Alauddin; ascended the throne after his father’s death. – Repealed many of Alauddin’s harsh policies but proved ineffective as a ruler. – Assassinated during his reign. |

| Nasiruddin Khusrau Shah | 1320 CE | – Hindu convert who took the throne after killing Mubarak Shah. – Short-lived rule; defeated by Ghazi Malik, who founded the Tughlaq dynasty as Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq in 1320 CE. |

| Ruler | Period | Key Contributions and Events |

|---|---|---|

| Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq | 1320–1325 CE | – Founder of the Tughlaq dynasty, also known as Ghazi Malik. – His father was a Qaraunah Turk, hence the dynasty is sometimes referred to as the Qaraunah Turks. – Established the strong fort of Tughlaqabad near Delhi. – Sent his son, Jauna Khan (later Muhammad bin Tughlaq), on military campaigns against the Kakatiyas in Warangal and the Pandyas in Madurai. – Relationship with Sufi saint Sheikh Nizam-ud-din Auliya was strained. – Believed to have been killed by Jauna Khan in 1325. |

| Muhammad bin Tughlaq | 1325–1351 CE | – Remembered for ambitious yet ill-fated experiments, often ahead of their time. – Capital Transfer: Moved capital from Delhi to Devagiri (renamed Daulatabad) to control southern India. The journey was arduous; many died en route. Abandoned Daulatabad after two years due to water shortages. – Token Currency: Introduced copper tokens in 1329, inspired by China. Tokens were easily forged, leading to economic losses and eventual withdrawal. – Taxation in the Doab: Imposed heavy taxes on farmers in the Doab during famine, leading to revolt. – Agricultural Reforms: Launched Takkavi loans for farmers and established Diwan-i-amir-Kohi, with limited success. |

| – Despite failures, was well-educated and tolerant of other religions. – Maintained diplomatic relations with Iran, Egypt, and China. – The famous traveller Ibn Battuta served as Qazi of Delhi during his reign. – Later years were marred by rebellions; the Sultanate of Madurai broke away, and the Vijayanagara Empire was founded in 1336, followed by the Bahmani kingdom in 1347. – Died in 1351; historian Barani described him as a “mixture of opposites,” marking the beginning of the Sultanate’s decline. | ||

| Firoz Shah Tughlaq | 1351–1388 CE | – Cousin of Muhammad bin Tughlaq; known for administrative reforms and public works. – Appointed Khan-i-Jahan Maqbal, a converted Telugu Brahmin, as wazir (prime minister), who played a key role in governance. – Military Campaigns: Focused on consolidating power in northern India; unsuccessful campaigns against Bengal leading to independence. Attacked Jajnagar (Orissa) and collected loot from temples. – Administrative Reforms: Ruled according to Islamic principles, revived the Iqta system, ensuring hereditary succession. Imposed jizya tax on non-Muslims but abolished certain taxes. |

| – Despite failures, was well-educated and tolerant of other religions. – Maintained diplomatic relations with Iran, Egypt, and China. – The famous traveller Ibn Battuta served as Qazi of Delhi during his reign. – Later years marred by rebellions; the Sultanate of Madurai broke away, and the Vijayanagara Empire was founded in 1336, followed by the Bahmani kingdom in 1347. – Died in 1351; historian Barani described him as a “mixture of opposites,” marking the beginning of the Sultanate’s decline. | ||

| – Irrigation Tax: First Sultan to levy an irrigation tax; built canals, wells, and gardens, boosting agricultural production. – Established new towns, including Firozabad (modern-day Firoz Shah Kotla in Delhi). – Repaired monuments like the Qutb Minar and Jama Masjid; brought Ashokan pillars from Meerut and Topra to Delhi. – Established Diwan-i-Khairat to assist orphans and widows, along with hospitals and marriage bureaus for poor Muslims. – Patronized scholars like Ziauddin Barani and authored Futuhat-e-Firozshahi. |

| Ruler | Period | Key Contributions and Events |

|---|---|---|

| Khizr Khan | 1414 – 1421 CE | – Appointed governor of Multan; seized Delhi after Timur’s departure, establishing the Sayyid dynasty in 1414 CE. – Preferred the title of Rayat-i-Ala over Sultan. – Made efforts to strengthen the Delhi Sultanate but faced numerous challenges and was largely unsuccessful. – Passed away in 1421 CE, leaving a weakened dynasty. |

| Mubarak Shah | 1421 – 1433 CE | – Son of Khizr Khan; succeeded him as ruler of the Sayyid dynasty. – His reign was marked by the continuation of instability and difficulty in maintaining control over the nobles. |

| Muhammad Shah | 1434 – 1445 CE | – Ascended the throne following Mubarak Shah’s death. – Faced internal conspiracies and gradually lost control over his nobles, leading to a decline in authority. – Died in 1445 CE, further destabilizing the Sayyid dynasty. |

| Alam Shah | 1445 – 1451 CE | – Son of Muhammad Shah; the last and weakest of the Sayyid rulers. – His wazir, Hamid Khan, invited Bahlul Lodhi to command the army, indicating a decline in power. – Chose to retire to Badaun amidst growing challenges to his rule, effectively ending his reign. |

The Lodhi (or Lodi) dynasty was the last to rule during the Sultanate period and the first Afghan-led dynasty. They initially governed Sirhind while the Sayyids ruled in Delhi.

| Ruler | Period | Key Contributions and Events |

|---|---|---|

| Bahlol Lodhi | 1451 – 1489 CE | – Established the Lodhi dynasty. – In 1476 CE, defeated the Sultan of Jaunpur and incorporated it into the Delhi Sultanate. – Brought Kalpi and Dholpur under Delhi’s control, and annexed the Sharqui dynasty. – Introduced copper coins known as Bahlol coins. – Died in 1489 CE; succeeded by his son, Sikander Lodhi. |

| Sikander Lodhi | 1489 – 1517 CE | – Considered the most prominent Lodhi ruler; extended his kingdom from Punjab to Bihar. – Subdued Rajput chiefs and forced the ruler of Bengal into a treaty after military engagement. – Known for administrative skills: built roads and developed irrigation systems for farming. – Introduced the Gazz-i-Sikandari (measurement system) and implemented an auditing system for financial records. – Re-imposed the Jiziya tax and destroyed temples, showing intolerance toward non-Muslims. – Founded the city of Agra in 1504 CE and wrote Persian poetry under the pen name Gulrakhi. |

| Ibrahim Lodhi | 1517 – 1526 CE | – Eldest son of Sikander Lodhi; ruled as a harsh and arrogant leader. – Treatment of nobles led to widespread dissatisfaction and rebellion; executed those who revolted. – Humiliated Daulat Khan Lodhi, the governor of Punjab, worsening relations. – Daulat Khan invited Babur to invade India due to discontent. – Defeated and killed by Babur in the First Battle of Panipat in 1526 CE, ending the Lodhi dynasty after 75 years of rule. |

The Iranian Pashtuns of the Lodi Tribe ruled the Lodi Dynasty. The Delhi Sultanate was already in decline by the time the Lodi took over. Sultan Sikandar Lodi relocated the Delhi Sultanate’s capital to Agra, which would go on to develop and flourish when the Delhi Sultanate ended. The last legitimate ruler of the Delhi Sultanate would be Ibrahim Lodi, the son of Sikandar. The height of political unrest under Ibrahim Lodi’s reign was the First Battle of Panipat in 1526, which saw the future Mughal Emperor Babur defeat Ibrahim Lodi and establish his dynasty in India.

The Delhi Sultanate, which spanned numerous centuries, became defined no longer as the most effective through its wealthy culture but also its problematic administration and governance systems. As kingdoms grew and fell, the administrative shape formed, having a long-lasting effect on the Indian subcontinent.

The Delhi Sultanate followed a controlled governmental system that placed significant energy within the fingers of the Sultan. At the top of this shape turned into the Sultan, who held each governmental and religious power. The Sultan’s choices were bound, and different governmental officials performed his will.

At the arterial heart of the executive form became the Sultan, who held the best authority in political and non-secular topics. The Sultan considered his orders as law, and he made final choices. This centralization of power allowed for quick choice-making and fast implementation of policies, allowing the Sultanate to respond to challenges and opportunities with speed.

The empire split into regions called “iqtas,” managed by a ruler chosen by the Sultan. These rulers, or amir-i-shikar, were responsible for keeping law and order, collecting taxes, and ensuring efficient working in their various areas. This decentralized method enabled powerful government and income collection throughout different regions.

The empire was divided into provinces referred to as “iqtas.” These provinces were further divided into districts, each headed with the aid of a governor known as an amir-i-shikar. This decentralized structure allowed for green governance and the collection of revenue.

The administrative structure protected numerous officers responsible for unique parts of government. The Diwan controlled sales and spending, ensuring economic security. Ariz-i-Mumalik became responsible for navy affairs, while Sadur handled spiritual topics.

The Sultanate’s monetary safety rested on the green income series. Land income, known as Kharaj fashioned a broad part of profits. The size of land, measurement of taxes, and tracking of sales series have been carefully done.

The Sultanate’s crime system became mainly based on Islamic principles, with Qazis (judges) allotting justice. Sharia courts’ status ensured Islamic law’s software in civil and crook topics, offering a feeling of justice and order.

The Delhi Sultanate left a profound impact on the governance and political landscape of India, influencing subsequent empires and shaping the region’s administrative practices. Here are some key aspects of its legacy:

The Delhi Sultanate established a model of centralized governance that emphasized the authority of the ruler. This system laid the groundwork for future empires, including the Mughal Empire, which adopted similar administrative structures.

The Sultanate’s military organization was highly structured, with a focus on maintaining a strong standing army. This emphasis on military power influenced later rulers in their approach to governance and territorial expansion.

The Delhi Sultanate implemented efficient revenue collection systems, including land revenue assessments. These practices were refined by later rulers and became integral to the economic administration of subsequent empires.

The incorporation of Shariat (Islamic law) into the legal system established a precedent for the integration of religious principles into governance. This influence persisted in various forms in later Islamic states in India.

The Sultanate fostered a unique blend of Persian, Indian, and Islamic cultures, which influenced administrative practices, art, and architecture. This cultural synthesis became a hallmark of governance in the region.

While the Sultanate was often characterized by nepotism, some rulers promoted merit-based appointments in administration and military, setting a precedent for future governance models.

The political structures and practices established during the Sultanate influenced regional powers and local governance, leading to a complex political landscape that persisted long after its decline.

The importance of the Delhi Sultanate cannot be overstated. It served as a bridge linking the East and the West, enabling alternate trade and the change of thoughts among one-of-a-kind sector components. The Sultanate’s effect on Indian society became deep because it provided new governmental structures, building marvels, and cultural changes that left a lasting imprint on the subcontinent’s past. The status of notable city centres such as Delhi, Agra, and Lahore added to the boom of a numerous and lively city lifestyle.

The Delhi Sultanate era witnessed a dynamic economic landscape. Here’s a closer look at the key aspects:

The Delhi Sultanate era introduced a blend of Indian and Islamic influences that significantly shaped architecture and culture. This period saw the emergence of domes and arches inspired by Indo-Islamic aesthetics. Additionally, advancements in technology contributed to textile innovations with the development of ginning (seed extraction), carding (fibre loosening), and spinning (yarn production), fostering growth in the textile industry.

These iconic structures reflect the fusion of artistic and cultural elements that defined the Delhi Sultanate era.

The Delhi Sultanate, a dominant force in Indian history, eventually went into decline, paving the way for a new empire. While its reign ended, its impact on the subcontinent was undeniable. Let’s explore the factors that led to the Sultanate’s fall and the enduring legacy it left behind.

The decline of the Delhi Sultanate wasn’t an abrupt end, but rather a gradual weakening that created an opportunity for a new dynasty to rise. In 1526, Babur established the Mughal Empire, marking a significant shift in the power structure of India.

Despite its decline, the Delhi Sultanate left an indelible mark on Indian culture. It introduced Islamic customs, traditions, and architectural styles. This rich blend with existing Indian elements gave birth to a unique “Indo-Islamic” culture that continues to shape the subcontinent’s identity today.

The Delhi Sultanate era also witnessed the flourishing of Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam. Sufi saints played a pivotal role in spreading Islam across India, not through force, but through their messages of love, tolerance, and spiritual enlightenment. Their influence transcended religious boundaries, attracting followers from diverse backgrounds and enriching the tapestry of Indian culture.

The Delhi Sultanate’s story may have ended, but its legacy continues to resonate in the cultural fabric of India. It’s a reminder that empires may rise and fall, but the impact they leave on society can be long-lasting.

The Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526) played a crucial role in shaping Indian history, particularly in governance and administration. Centered in Delhi, its rule extended across South Asia, leaving a lasting impact on politics, culture, and architecture.

The Sultanate went through five dynastic phases, each contributing uniquely to its legacy. Its foundation was influenced by Turkic migrations from Central Asia during the Middle Ages, which integrated various ethnic groups into its administration. The first ruler, belonging to the Mamluk Dynasty, reflected this diverse and dynamic origin of the Sultanate.

Throughout its reign, the Delhi Sultanate played a crucial role in shaping the socio-political landscape of South Asia. Its governance, marked by administrative reforms, cultural exchanges, and architectural marvels, left a lasting impact on the region. Despite its eventual decline in 1526, the Delhi Sultanate’s legacy endures, serving as a pivotal period in India’s history and a subject of study for aspirants preparing for the UPSC examination.

The management and governance systems of the Delhi Sultanate have been varied, mirroring the difficulties of a kingdom that spanned centuries and covered different cultures. The unified administrative structure, local divisions, and key officials reinforced the Sultanate’s commitment to efficient government. The income collection machine, law framework, army company, and culture favour jointly added to the Sultanate’s enduring legacy.

Ans. In 1206, Qutub ud-din Aibak was the first monarch and founder of the Delhi Sultanate.

Ans. Ibrahim Lodhi was the final monarch of the Delhi Sultanate. In 1526, he was defeated by Babur at the Battle of Panipat.

Ans. The administration was founded on Shariat or Islamic regulations during the Delhi Sultanate.

Ans. Under the Delhi Sultans, Persian was the language of government.

Ans. There was a total of five dynasties that reigned in the Delhi Sultanate.

Ans. Qutubuddin Aibak assumed the role as the inaugural ruler of the Delhi Sultanate.

Ans. After the Ghurid dynasty invaded South Asia, the Delhi Sultanate was controlled by five dynasties in succession: the Sayyid dynasty (1414–1451), the Lodi dynasty (1451–1526), the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414), the Mamluk dynasty (1206–1290), and the Khalji dynasty (1290–1320).

Authored by, Amay Mathur | Senior Editor

Amay Mathur is a business news reporter at Chegg.com. He previously worked for PCMag, Business Insider, The Messenger, and ZDNET as a reporter and copyeditor. His areas of coverage encompass tech, business, strategy, finance, and even space. He is a Columbia University graduate.

Editor's Recommendations

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.

Chegg India does not ask for money to offer any opportunity with the company. We request you to be vigilant before sharing your personal and financial information with any third party. Beware of fraudulent activities claiming affiliation with our company and promising monetary rewards or benefits. Chegg India shall not be responsible for any losses resulting from such activities.